A new laser technology discovered tens of thousands of residences, tombs and palaces belonging to the Mayan civilization buried under the thick Guatemalan jungles. Archaeologists are stunned by the sheer scale of the discovery and believe that it will change everything that the world knows about the lost civilization.

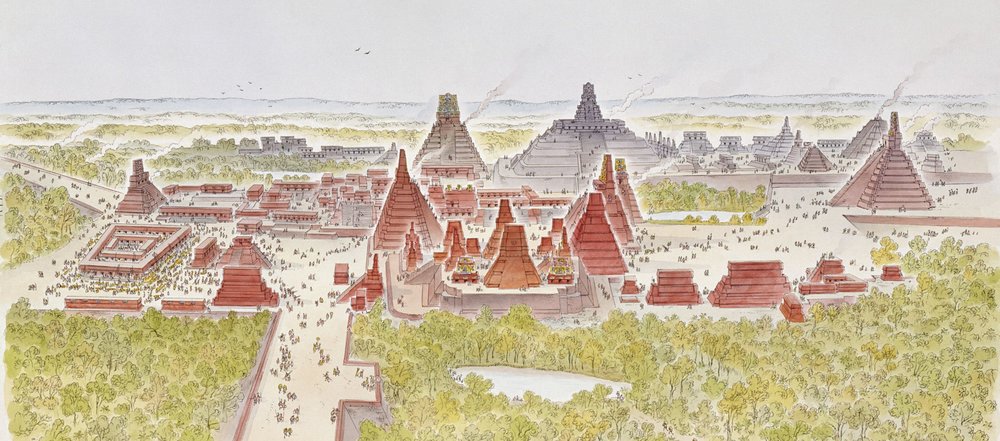

A graphic indicating how the recently-discovered ancient city looked like

Discovery of the Largest Mayan Settlement

Scientists and archeologists have shown a special interest in studying the Mayan world which had ceased to exist more than a millennium ago. For years, researchers have tried to unearth new settlements buried deep underground but a recent discovery of almost 600,000 houses, tombs and palaces shielded by the northern jungles of Guatemala has surprised the archeologists who weren’t ready to uncover a settlement of such a large scale.

This new discovery was made close to the sites that are already popularly visited by tourists worldwide, and the laser technology used to locate the settlement also uncovered an intricate road and highway system which proved that the lost civilization was too advanced for their time.

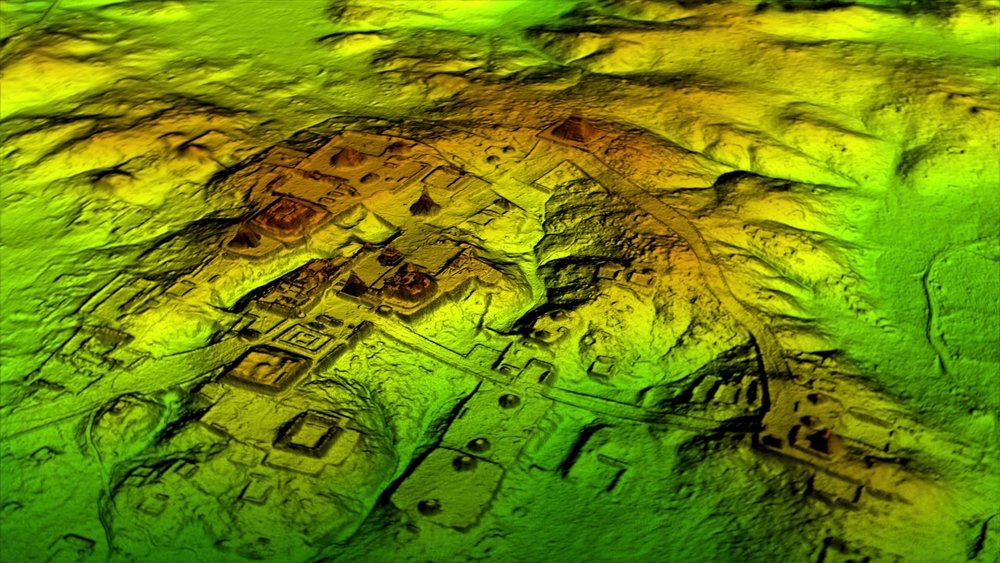

How the lost Mayan city appears to be via the new technology, lidar

Archeologists, who made the discovery, couldn’t believe the sheer volume of houses, buildings and tombs which somewhat resembled the city of Tikal but with a greater density and more advanced interconnectedness than any settlement ever found before.

A Promising Laser Detection Technology

The new technology, called lidar or Light Detection and Ranging, enabled archeologists to shoot lasers from a plane high above the ground to enter through the dense foliage and create an accurate 3D map of the settlement buried underneath the ground.

Several smaller settlements around the popular Angkor Wat temple in Cambodia have already been discovered before using the technology, but this latest discovery is bigger than any other lidar project in the history, uncovering a settlement in Guatemala’s Maya Biosphere Reserve spanning over 800 square miles.

The reports of the discovery were first made public by National Geographic which is airing a special television documentary today to unveil the details of the project.

Nonprofit organization Pacunam aims to scan the entire area in the Maya Biosphere Reserve using lidar in hopes of unearthing more Mayan secrets buried underground.

$600,000 Spent on the Project So Far

Albert Yu-Min Lin, an experienced explorer who worked with Nat Geo on creating the special documentary, says that he is thrilled by the discovery of the recent data which opens doors for archaeologists to peek into the Mayan world with an accuracy that didn’t exist before.

However, Lin still has the difficult task of verifying the data found through the lidar project by trekking through the difficult terrain of the Guatemalan jungles and finding evidence of the archeological goldmine buried underneath.

The expensive lidar project which was started by a nonprofit organization named Pacunam has cost researchers over $600,000 on the initial phase. More money is expected to be raised for further stages of the discovery as other research organizations and universities get on board with the exciting undertaking.

The laser technology used in the project works by entering the earth and finding any bumps in an otherwise smooth landscape. To a normal person, the buried ruins inside the ground seem nothing more than mounds of rocks, but experienced archeologists are able to study the collapsed structure and tell if it was once a palace, house or a tomb.

Part of a Much Bigger Project

The first laser planes flew over the Maya Biosphere Reserve in 2016 and the researchers have been accumulating data for almost a year to create an accurate 3D picture of what lies underneath the ground.

The Guatemalan lidar project is only a small part of a bigger effort made by the non-profit organization to reverse climate change and protect their historic lands from deforestation and illegal activities. Pacunam is calling it a ‘Guatemalan effort’ which will unveil scientific goldmines as well as find a sustainable life for those who live in the historic area.

The Mayan civilization, which was at its peak from A.D. 250 to 900, is of special interest to archaeologists due to its advanced agricultural approach, and the latest findings have drawn an even better picture of the lost world. The 3D maps show complex road and wide highway structures used to connect markets and field to metropolises as well as highly developed irrigation systems for farmers.